Recursion has always been a tough concept to wrap my head around. My main flaw in trying to understand it was not visualising it as a tree unrolling. Maybe my obsession with imperative programming paradigm could be to blame for this. Ever since I started to visualise recursion as a method to brute-force the search space using clones, I have been able to write recursive code better.

Julie Zelenski’s Stanford Lectures do an amazing job of making you understand recursion. Her Programming Abstractions Course (CS106B) is an amazing place to start for those struggling with recursion or computer science fundamentals in general. Her lectures are quite engaging and she succintly explains the core concepts. The videos are available on YouTube. She explains recursion in videos 8-11.

This blog shall go through each of her recursion videos and summarize the core ideas through my Python implementation of the algorithms.

Introduction

What’s recursion?

- Recursive functions call themselves….duh 🤷♂️

- Solve problems using co-workers or CLONES 🔑

- For problems which exhibit Self-Similarity 👈

We spawn smaller instances of the same function doing the same task on smaller input/ problem.

Base Case is when the input/problem is so small that we don’t need another task repeating clone

She then goes on to define Functional Recursion

- Function that returns answer or result

- Outer problem result ⬅ Result from smaller same problem

- Base case

- Simplest version of problem

- Can be directly solved

- Recursive case

- Make call to self to get results for smaller, simpler version

- Recursive calls must advance towards base case

- Results of recursive calls combined to solve larger version

Exponential problem

baseexp = base * baseexp-1

Python code to achieve this would be:

def exp(base,power):

if power==0:

return 1

return base * exp(base,power-1)

How many recursive cases will be called before base case?

There’ll be power number of recursive calls. Let’s say time complexity is O(N)

Can we make it more efficient?

🤔 Well yeah, there’s a way. Consider this property:

baseexp = baseexp/2 * baseexp/2

Now a question might arise….what about odd powers?

Well….for odd powers it’ll be something like this:

baseexp = base * baseexp/2 * baseexp/2

Remember that we are considering absolute division of the powers here

Python code to achieve this would be:

def exp(base,power):

if power==0:

return 1

val = exp(base,power/2)

if power%2==0:

return val*val

else:

return val*val*base

If you’re a bit confused about this, then think of it as you are decomposing for even power always

base5 = base4 * base

Hence, if odd multiply with an additional base.

This algorithm will be faster with a time complexity of O(log N)

Julie cautions against arm’s length recursion.

An example would be:

def exp(base,power):

if power==0:

return 1

if power==1:

return base

return base* exp(base,power-1)

Aim for simple and clean base case

- Don’t anticipate earlier stopping points

- Avoid looking ahead before recursive calls, let simple base case handle

Just let the code fall through

All recursive problems have a pattern. Our goal should be to find that pattern and use clones to solve the problem.

Palindrome Problem

The pattern of a palindrome is that if first and last letters match then it’s a palindrome if the inner substring is also a palindrome.

If we consider a word like sasas.

s [asa] s

a [s] a

Our base case would be if we were left with one or none character.

Python code for this would be:

def palindrome(string):

if len(string)<=1:

return True

if string[0]==string[-1]:

return palindrome(string[1:-1]

else:

return False

One way of formulating a recursive solution is to get a base case and test it, then consider one layer out( one recursive call out ).

You can think as it works for 0, it works for 1, it works for 2, take a leap of faith ,it works for n, it works for n+1.

This idea is very similar to bottom-up dynamic programming.

Binary Search

This classic decrease and conquer problem can be solved both iteratively and recursively. However recursive solutions are always elegant and short pieces of code.

Python code for this would be:

n = len(array)

def binary_search(array,key,start=0,end=n-1):

mid = (start+end)//2

if array[mid]==key:

return True

if start>end:

return False

if array[mid]>key:

binary_search(array,key,start,mid-1)

else:

binary_search(array,key,mid+1,end)

Some may get confused with the following base-case:

if start>end:

return False

When the key is not present in the array, we will reach a stage where start=n and end = n+1. In such a case, mid = n. This will make our new start = n+1 and end = n+1 reamains same. This time our mid=n+1 and new start = n+2 but end remains n+1. Hence, the base case gets triggered.

nCk

Let’s consider the N Choose k problem. This one can get a bit tricky to formulate a recurrence relation at first. Upon closer inspection we get:

nCk = n-1Ck + n-1Ck-1

To make this clear, consider there are N balls. You have to pick K balls.

You can take a ball A, there are N-1 balls left. You can pick K balls from N-1 balls remaining or you can include ball A and pick K-1 balls from N-1 remaining balls.

Python code for this would be:

def choose(n,k):

if k==0 or k==n:

return 1

return choose(n-1,k) + choose(n-1,k-1)

Our base case here is no choices remaining at all! hence we check k==0 or k==n.

Consider picking k items as a task, when k=0 it means we have picked k items and have finished the task. Hence we return 1 to signify we finished one task. There’ll be many such task and we are interested in finding the total number of tasks i.e. combinations.

Well we have summarized lecture 8. Hang on! We have 3 more to go 😂

Thinking Recursively

Challenges and how to tackle them

- Recursive Decomposition

- Find recursive sub-structure

- Solve problem from subproblems * Identify base case

- Simplest possible case, easily solvable, recursion advances to it

- Common Patterns to solve

- Handle first and/or last, recur on remaining

- Divide in half, recur on one/both halves

- Make a choice among options, recur on updated state

- Placement of recursive calls

- Recur-then-process versus Process-then-recur

Types of recursion

Recursion can be broadly classified into procedural and functional.

- Functional Recursion

- Returns result

- Procedural Recursion

- No return value

- Task accomplished during recursive call

Drawing a fractal like Sierpinski triangle is an example of procedural recursion.

We are not returning anything but are achieving the drawing of the fractal during recursion.

You can copy Sierpinski Triangle python code here and paste below in main.py to visualize:

Try changing the order of the recursive calls and you’ll see the order of drawing change. This is because the tree is being unrolled differently.

Tower of Hanoi

This problem can be envisioned as moving n-1 disks to temporary using destination and moving the nth disk to destination. We then move the n-1 disks onto nth disk in destination using source as temp.

The Python code for this would be:

moves = 0

def MoveTower(n,src='source',dst='destination',tmp='temporary'):

if n<=0:

return

global moves

moves+=1

MoveTower(n-1,src,tmp,dst)

print('Move Disk {} from {} to {} using {}'.format(n,src,dst,tmp))

MoveTower(n-1,tmp,dst,src)

This algorithm has exponential time complexity of O(2N).

Time Complexity for a recursive function can always be calculated solving a recurrence relation.

T(N) = T(N-1) + T(N-1) = 2* T(N-1)

If we keep continuing till N=0, we get T(N) = 2N

Obviously if we were reducing the input by half instead of one like in binary search, it’ll differ.

T(N) = T(N/2) => 2x = N => x = log2N

Hence we say binary search time complexity is O(log2N)

But in the case of merge sort we need to consider the N comparisions being made during merge.

Hence, it’s equation would be:

T(N) = 2* T(N/2) + O(N) where O(N) is the max number of comparisions before merging the divided arrays.

Solving this following same steps as before gives us,

T(N) = 2log2N + ∑log2N O(N)

T(N) = N + O(N) * log2N = O(N log2N)

Well this math was unexpected 😅

Anyways now that we have a basic idea of recursion, let’s move on to next lecture about permutations(it’s present in current lecture too) and subsets.

Permutations and Subsets

When I started off this post, I wrote how recursion is a way to call the same function to achieve bruteforce. If you look at most recursive problems, they are actually a variant of finding permutations or finding subsets.

Now I know some of you might get confused with permutations or conflate it with combinations. 😵

Let’s first understand what’s permutation.

Permutation Problem

Let’s consider a string: “ABCD”

It’s permutations would be DCBA, CABD, etc.

Solving Recursively

- What is the output?

- Choose a letter and append it to output from input

- How do we ensure each letter is used once?

- What is the base case?

If we were to write code, we would want to select a character S[i] from string S, generate substring S[:i]+S[i+1:] and prepend S[i] to all permutations of the substring S[:i]+S[i+1:]. Base case would be when substring S[:i]+S[i+1:] is empty. We repeat this for all characters in index i=0…n to get permutations of string S.

Let’s use a procedural recursion where we don’t return and just print the permutations.

The Python code for this would be:

inp = 'abcd'

def permutation_print(StringSoFar, RemString):

'''

Input: String explored so far, Remaining string to use

Func: Procedural Recursion where we print out all strings

Output: None

'''

if len(RemString)==0:

print(StringSoFar)

for idx,char in enumerate(RemString):

NewStringSoFar = StringSoFar + char

NewRemString = RemString[:idx]+RemString[idx+1:]

permutation_print(NewStringSoFar, NewRemString)

permutation_print('',inp)

Copy this code and paste it in main.py and run it

Now you may be thinking, what if I want to store the values. I want to verify if I got the correct answer by checking the length of the array. 😏 Not an issue. We can return lists instead of printing.

inp = 'abcd'

def permutation(inp):

'''

Input: String

Func: For each letter in input, we recurse with remaining letters

Output: List of Permuted Strings

'''

if len(inp)==0:

return ['']

permutations = []

for idx,char in enumerate(inp):

new_inp = inp[:idx]+inp[idx+1:]

strings_so_far = permutation(new_inp)

strings_so_far = [char+string for string in strings_so_far]

permutations.extend(strings_so_far)

return permutations

res = permutation(inp)

print(len(res))

for i in res:

print(i)

Try running this above. You’ll get 24 as the length of our result array which is 4!

A question might arise now….what if input was aba i.e. input consists of repeating characters. We will repeated computation again on already visited characters. In that case our above algorithm will give duplicates like two aba instead of one. What do we do? Well we can put a condition where we check that if we have encountered a character already we skip through if we encounter it again.

The modified Python code would be:

inp = 'aba'

def permutation(inp):

'''

Input: String

Func: For each letter in input, we recurse with remaining letters

Output: List of Permuted Strings

'''

if len(inp)==0:

return ['']

permutations = []

visited = set()

for idx,char in enumerate(inp):

# Checking if we char is visited already

if char in visited:

continue

visited.add(char)

new_inp = inp[:idx]+inp[idx+1:]

strings_so_far = permutation(new_inp)

strings_so_far = [char+string for string in strings_so_far]

permutations.extend(strings_so_far)

return permutations

res = permutation(inp)

print(len(res))

for i in res:

print(i)

The same logic can be extended to list as input.

This recursion follows a choice pattern i.e. make a choice and do recursion and aggregate the results.

Hmmmm, are you still having difficulty understanding the recursion? It’s okay. Recursion is tricky 😄

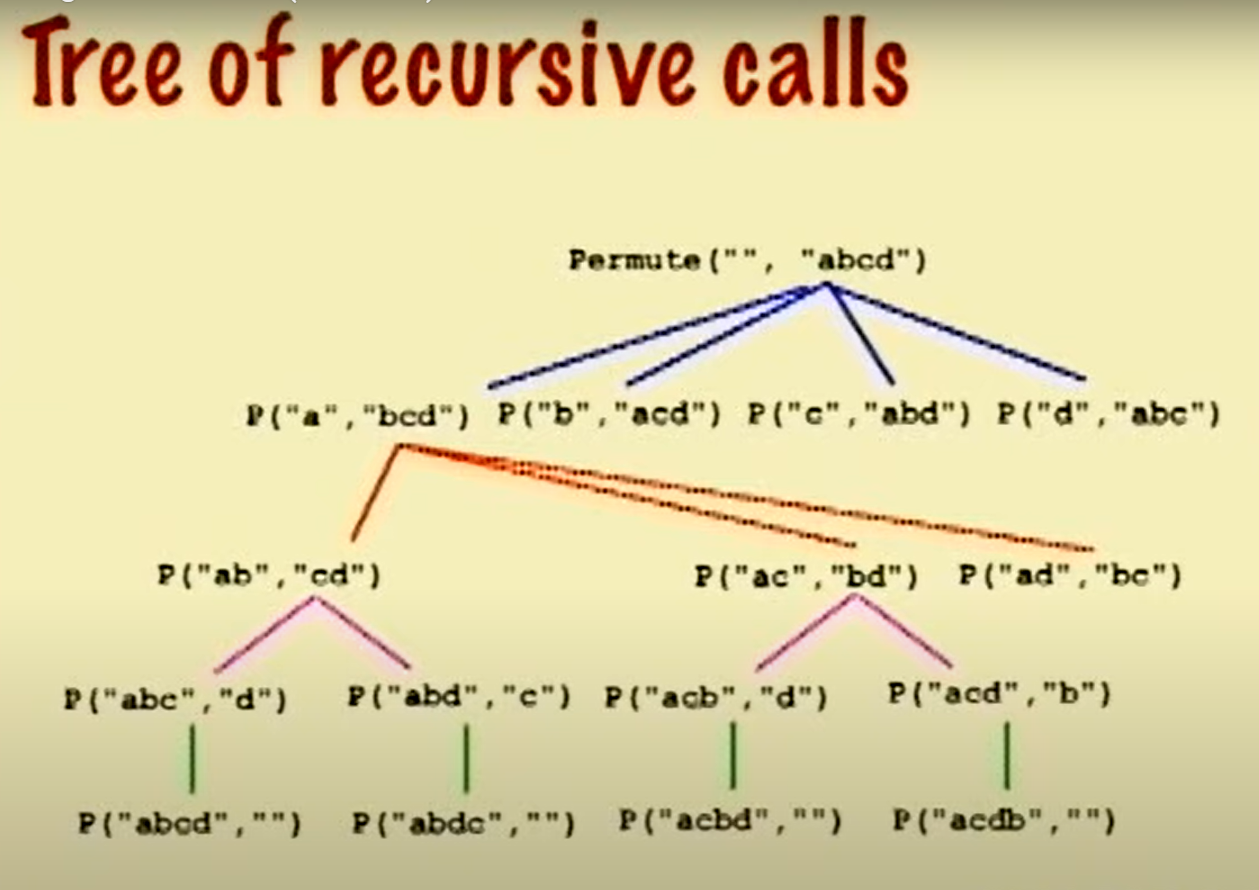

This tree diagram will help you understand better:

Permutation is a master pattern of recursion as there are many problems which can be reduced to a permutation problem.

Let’s explore the other master pattern : subsets

Subset Problem

Let’s consider a string: ABC

It’s subsets would be ABC, AB, BC, CA, A, B, C

Solving Recursively

- What is the output?

- Separate an element from the input

- Call adding element to output (Subsets with element)

- Call without adding element to output (Subsets without element)

- What is the base case?

Have we seen similar problem before? 🤔

Well….same patterns often resurface….nCk 😵

Just as before, we will focus on both the procedural and functional implementations of the solution.

inp = 'abcd'

def subset(string_so_far, rem_string):

if len(rem_string)==0:

print(string_so_far)

return

char = rem_string[0]

subset(string_so_far+char,rem_string[1:])

subset(string_so_far,rem_string[1:])

subset('',inp)

Functional recursion to store all the subsets in a list consists of add the current character to all subsets of remaining string.

Python implementation for it would be:

inp = 'abcd'

def subset_list(string):

if len(string)==0:

return ['']

first_char = string[0]

rem_string = string[1:]

child_subsets = subset_list(rem_string)

curr_subsets = []

curr_subsets = [first_char + i for i in child_subsets]

curr_subsets.extend(child_subsets)

return curr_subsets

print(subset_list(inp))

The 🔑 here is the base-case. return [’’] is important to get individual character subsets. You can run the code in the interpreter below.

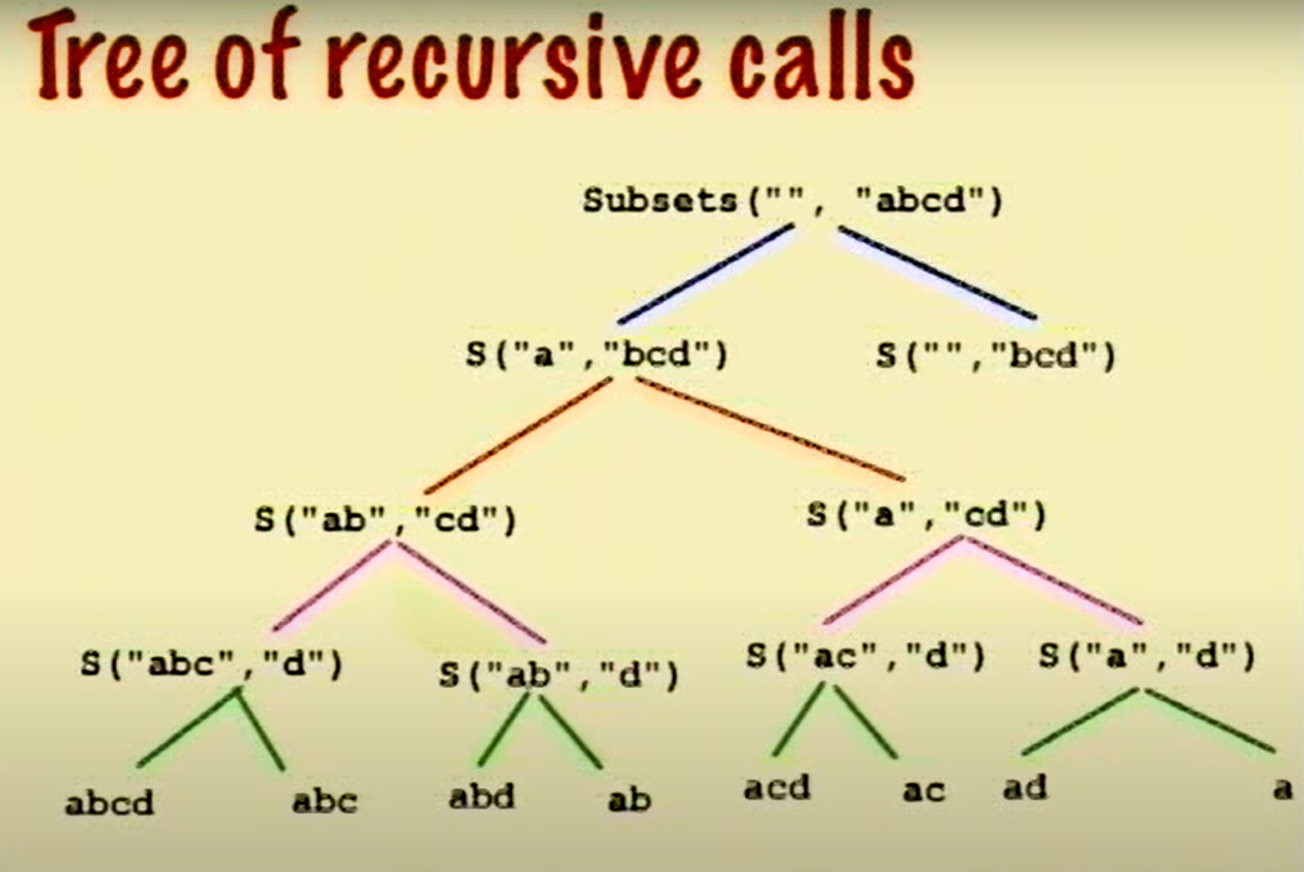

The following tree diagram will help you understand this better:

Subset has just one or two recursive calls whereas we have a for loop for permutation.

Permutation and Combination are master patterns. Mastering these will help you solve many problems.

These algorithms are examples of Exhaustive Search.

They are about choice. They have deep and wide trees. Depth is number of decisions made. Width is branching i.e number of options available per decision.

Every possible option is explored.

Time Complexity

Subset: 2N

Permutation: N!

When search space is too big, it takes forever if we use brute-force.

We can tackle this using the concept of recursive backtracking.

Recursive Backtracking

Instead of using brute-force and trying to explore the entire search space, we can consider some cases and check each case. If the check fails, we come back and consider the next case.

- Cast problem in terms of decision points

- Identify the decisions to be made

- Identify options available for each decision

- Recursive call makes one decision and recurs on remaining decisions

- Backtracking approach

- Design recursion function to return success/failure

- Each call choose one option and go

- Recursively proceed and see what happens

- If it works out ,great, otherwise unmake choice and try again

- If no option worked, return fail result which triggers backtracking (i.e. un-making earlier decisions)

- Heuristics may help efficiency

- Eliminate dead ends early by pruning

- Pursue most likely choice first

In short, make a choice and go with it. Doesn’t work out? Fine. Proceed with the other choices

Almost all backtracking algorithms have the following pseudo-code:

def Solve(configuration):

if (no more choices) // Base Case

return (configuration is goal state)

for (all available choices):

try one choice c:

// solve from here, if it works out, you're done

if Solve(configuration with choice c made) return True

// If it returns false we unmake our choice

unmake choice c

return False // tried all choices, no soln found

The pseudo-code is pretty self explanatory.

N-Queens Problem

The problem is pretty simple. We have a NxN board. We need to place a queen Q in each column such that no two Q’s are in conflict with one another.

This problem can be solved using recursive backtracking.

The positions to place in a column are the choices we have at hand.

If a conflict occurs we check other choices i.e. positions in a column. If all positions are unsatisfiable we return False to previous call initiating backtracking it the parent recursive call.

If we are able to find one configuration such that the current column is greater than the last column, it means we have achieved a satisfiable configuration for all the columns.

The python code for this would be:

n = 8

board = [[' ' for i in range(n)] for j in range(n)]

# We consider rows of our board as columns of actual board. Our board is flipped.

# We keep track of the current column with col parameter

def recurse_backtrack(board,col=0):

if col>n-1:

return True

for position in range(n):

board[col][position] = 'Q'

flag = 0

# Checking for conflicts with previous columns

for prev_col in range(0,col):

prev_position = board[prev_col].index('Q')

if prev_position == position or abs(prev_position-position)==abs(prev_col-col):

flag = 1

# If conflict check other choices

if flag:

board[col][position] = ' '

continue

# If current choice holds true

if recurse_backtrack(board,col+1): return True

# If current choice is false remove Queen

board[col][position] = ' '

# Run out of choices

return False

recurse_backtrack(board)

for i in board:

print(i)

Try running it in the above interpreter.

You’ll get the same answer every time you run it because the order of tree unrolling will remain constant.

You can change the ordering of the positions in for loop to get a different answer.

Yawn…..Almost finished 🥱. One video left. Let’s finish 💪

Conclusion

Little More Backtracking

Julie discusses about sudoku solver. She talks about a brute force recursive solver that explores the entire search space. It is a classic backtracking problem. We just need to handle the domain-specific cases which is checking if there is no conflict in row, column or subgrid of the sudoku.

The Python implementation of the problem would be:

n = 9

board = [[-1 for i in range(n)] for j in range(n)]

[print(i) for i in board]

while True:

print('Enter Row,Col,Value! Type quit to quit!')

a = input()

if a == 'quit':

break

a = a.split(',')

if len(a)<3 or len(a)>3:

print('Enter 3 values separated by ,')

continue

a = [int(i) for i in a]

row,col,value = a[0],a[1],a[2]

if row in range(n) and col in range(n) and value in range(10):

board[row][col] = value

[print(i) for i in board]

else:

print('Enter valid values')

org_board = board.copy()

def subgrid_check(board,value,row,col):

row_factor = row//3

col_factor = col//3

row_square_start = row_factor*3

row_square_end = row_square_start+3

col_square_start = col_factor*3

col_square_end = col_square_start+3

vals = [board[i][j] for i in range(row_square_start,row_square_end) for j in range(col_square_start,col_square_end)]

if value in vals:

return False

else:

return True

def col_check(board,value,col):

vals = [i[col] for i in board]

if value in vals:

return False

else:

return True

def row_check(board,value,row):

vals = [i for i in board[row]]

if value in vals:

return False

else:

return True

def sudoku_solver(board,number=0):

n=len(board)

total = n**2-1

if number>total:

return True

row = number//n

col = number%n

value = board[row][col]

if not value==-1:

return sudoku_solver(board,number+1)

for i in range(1,10):

if col_check(board,i,col) and row_check(board,i,row) and subgrid_check(board,i,row,col):

board[row][col] = i

if sudoku_solver(board,number+1):

return True

else:

board[row][col] = -1

return False

res = sudoku_solver(board,0)

for i in board:

print(i)

Copy and run it below

Think of backtracking as a conversation between a boss and their delegate over a puzzle.

Boss: Hey I’m giving you this, solve it for for me

Delegate: I tried everything, nothing worked

Boss: Oh Okay, let me check. Maybe I gave you something wrong. Let me check it from my end.

Boss: Here you go I changed it. Solve it now.

Delegate: I found the solution.

If you consider your problem as a decision-making problem, it can always be written using recursive backtracking.

Looking for Patterns

Most problems have common patterns. If we have find the common pattern and reduce the problem to a problem we know, it makes finding the solution easier. This is why permutation and subset problems are considered as master patterns.

- Knapsack Problem ➡ Subset

- Travelling Salesman ➡ Permutation

- Dividing into teams with similar IQ ➡ Subset

- Finding longest word from sequence of letters ➡ Subset + Permutation

Practicing recursion is the best way to get better at it as there are many intricacies involved with each problem which we can learn to solve efficiently only through repeated practice. However the concepts we explored form a crucial foundation for us. Just remember that recursion is ideal only when our input size is reducing each call till we are left with nothing at the base case. There will be cases where it makes no sense to solve with recursion. A classic example would be BFS implementation with recursion. BFS is not inherently recursive hence, no point implementing it as a pure recursive call without any auxilliary data structure.

Recursion is all about decision making with given options and calling a clone to do the same on reduced search space.

👏🙌 Well we finished it! That was a lot to digest if you lost touch with recursion or are refreshing it. I will keep writing such technical blogs. Stay tuned 🔍. 👋